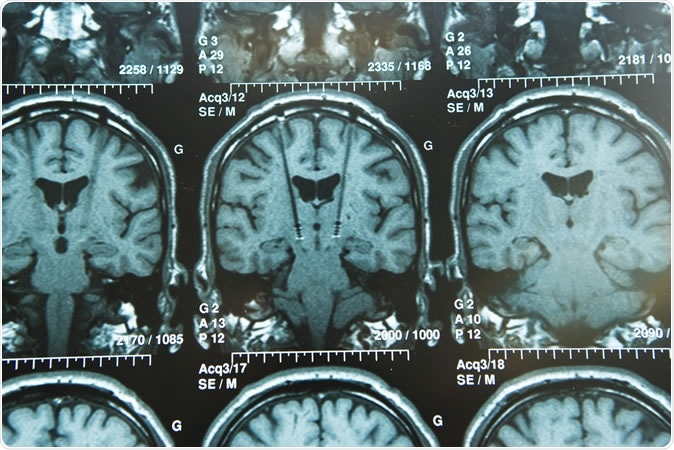

Daniel Waldvogel, MD, of the University of Zurich in Switzerland, explained about the cases saying, “Until more research is done to determine why some people with deep brain stimulation can no longer swim, it is crucial that people be told now of the potential risk of drowning and the need for a carefully supervised assessment of their swimming skills before going into deep water.” The team explained that for this surgery the doctors place electrodes deep inside certain areas of the brain and this can help control the abnormal movements of the body. A device can help stimulate these electrodes from outside by sending electric impulses wrote the researchers. The external device is implanted under the skin of the chest.

The team writes that of these nine individuals, three had improved significantly after the electrode implantation. Their movements and symptoms of Parkinsonism had markedly improved.

One of them was a 69-year-old man who used to be a good swimmer who lived by a lake. After his deep brain stimulation, according to his previous habit, he had jumped into the water hoping to swim. He had to be rescued by a family member before he could drown wrote the researchers. “Feeling confident after DBS because of his good motor outcomes, he literally jumped into the lake where he would have drowned if he had not been rescued by a family member,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Another was a 59-year-old woman who used to be a competitive swimmer and continued swimming even after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. After the implantation of the electrodes, she was unable to swim again. She sought help from a physiotherapist and learned to swim again. But her form remained below her initial level wrote the researchers.

The third was also a 61-year-old female who was a competitive swimmer. After her electrode implantation, she said her posture became awkward and she could not swim anymore. As soon as they turned off the electrodes inside their brains, they could swim again report the researchers. The symptoms of Parkinson’s disease also returned as they switched off the electrodes and all three of the patients had to switch the devices on again wrote the researchers.

Study co-author Dr. Christian Baumann, an associate professor in the department of neurology at the University Hospital of Zurich in Switzerland, in his statement, said, “Neurologists and patients should be aware of this potential effect of DBS, even if it’s rare.” He added that the permanence of this effect is not yet clear. He said in his statement, “Turning off DBS improves swimming, as experienced by some patients, but other motor functions get worse so that patients always turn the DBS on again.

Still, they can learn swimming again, but maybe not at the same level as before.” Baumann and his colleagues reported this study as part of their large ongoing study that looked at implantation of the electrodes in 217 patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Waldvogel said in a statement, “Swimming is a highly coordinated movement that requires a complicated arm and leg coordination. Exactly how deep brain stimulation is interfering with this ability needs to be determined.”

Baumann explained why this phenomenon was happening saying, “It most probably has to do with the fact that (alteration) of synchronized action in different brain structures impairs some complex motor behaviors that have been learned in the past. Thus, imprinted learned or orchestrated brain activity is to some extent changed.”

Other experts have said that only a small proportion of those getting deep brain stimulation are unable to swim. This study may alarm others about the effects of DBS and prevent them from opting for this treatment modality that could benefit them. Waldvogel added that this was a small case series and larger studies are needed to be certain of an association between deep brain stimulation and losing the ability to swim. He said, “Even though these reports affected only a few people, we felt this potential risk was serious enough to alert others with Parkinson's disease, as well as their families and doctors.”

Journal reference:

Beware of deep water after subthalamic deep brain stimulation Daniel Waldvogel, Heide Baumann-Vogel, Lennart Stieglitz, Ruth Hänggi-Schickli, Christian R. Baumann Neurology Nov 2019, 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008664; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008664, https://n.neurology.org/content/early/2019/11/26/WNL.0000000000008664.

No comments

Post a Comment