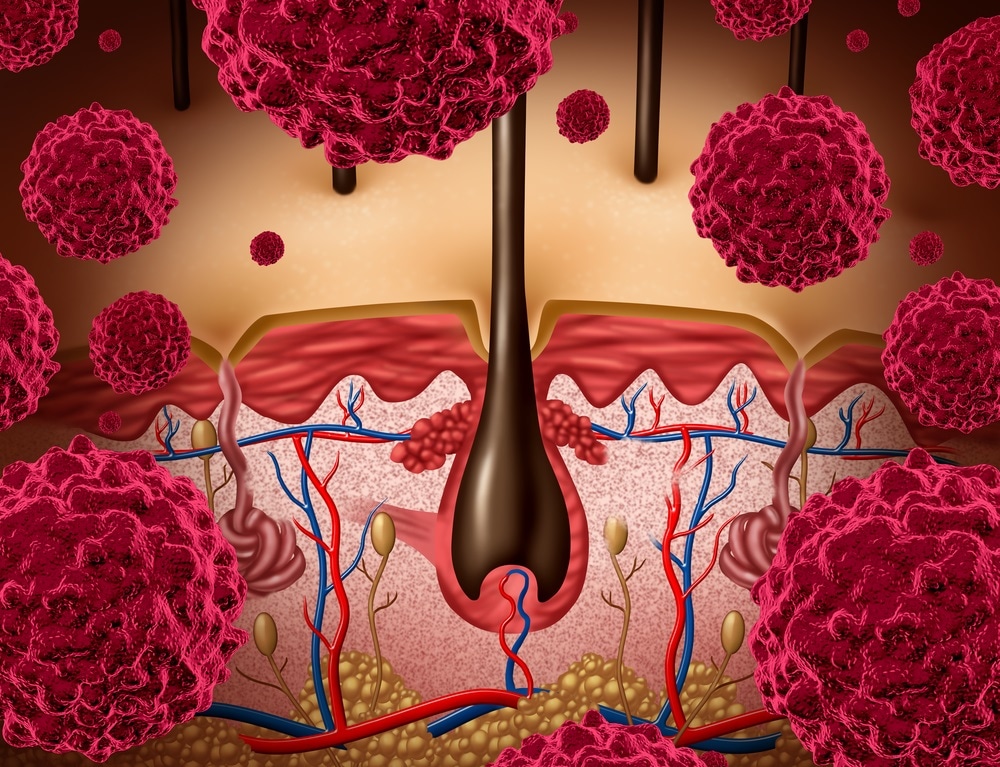

Some deadly skin cancers may originate in the pigment-making stem cells in hair follicles rather than in skin, according to researchers at the NYU School of Medicine and Perlmutter Cancer Center.

The team’s study showed that immature stem cells within hair follicles acquire oncogenic changes before then responding to normal hair growth signals.

Previous models of skin cancer had suggested that sunlight is the major risk factor for melanoma, but the current study suggests that triggers for the disease are always present in normal hair follicles.

Oncogenic pigment-making stem cells migrate from hair follicles into skin

A new study published in the journal Nature Communications showed that unlike their healthy counterparts, oncogenic pigment-making stem cells move from hair follicles into the surrounding skin and establish melanomas before spreading deeper into the skin.The researchers initially used genetically engineered mice to establish hair follicles as a source for melanoma and then confirmed their findings using human tissue samples.

"By confirming that oncogenic pigment cells in hair follicles are a bona fide source of melanoma, we have a better understanding of this cancer's biology and new ideas about how to counter it,"

Mayumi Ito Suzuki, study author

The researchers came to their conclusion after studying the process through which an embryo, which is a single stem cell, develops into a fetus, which is made of hundreds of different types of cells. During this development, stem cells divide, proliferate and become specialized into cells capable of performing just one role such as a nerve cell or skin cell.

Flexibility of stem cells can be dangerous in adults

However, stem cells can mature into more than one type of specialized cell and are capable of shifting between the different cell types. Although useful during embryonic development, this flexibility can be dangerous in adults because cancer cells are thought to regain features of immature embryonic cells. This has led researchers to question whether melanoma may originate in several types of stem cells, which would make it more difficult to monitor and treat.The current study looked at stem cells that become melanocytes – the cells that produce melanin to protect skin by absorbing the ultraviolet rays that damage DNA. By soaking up some visible light rays, but not others, these cells create hair pigment.

Suzuki and the team used a new mouse model of melanoma in which they could edit genes in follicular melanocyte stem cells only. They introduced genetic changes that would make melanocyte stem cells, as well as their descendants that were destined to form melanomas, glow upon migration.

Accurately tracking stem cell migration

With this new ability to accurately track stem cell migration, the team was able to confirm that melanoma cells arise from melanocyte stem cells that travel up and out of hair follicles and into the skin’s outermost layer - the epidermis. Next, the researchers monitored the cells as they multiplied in the epidermis and then moved lower down into the dermis.Once in the dermis, the cells released the markers and pigment that they had in hair follicles, presumably in response to growth signals. They also acquired signals resembling nerve and skin cells, molecular features that were almost the same as those observed in studies of human melanoma.

Once the researchers knew where to find the initial oncogenic event, they started to remove signals in hair follicles one by one to see whether melanoma still formed without them.

This enabled the team to confirm that even if melanocyte stem cells in hair follicles had acquired cancer-causing genetic changes, they did not proliferate or migrate to form melanomas unless they were exposed to the signaling proteins WNT and endothelin. These proteins usually cause hairs to lengthen and follicular pigment cells to multiply.

The first model to show this

First author Qi Sun says the team’s mouse model is the first to show that follicular oncogenic melanocyte stem cells can establish melanomas and that it will be useful for identifying new diagnostics and treatments for melanoma."While our findings will require confirmation in further human testing, they argue that melanoma can arise in pigment stem cells originating both in follicles and in skin layers, such that some melanomas have multiple stem cells of origin," concludes Qi.

Some skin cancers may start in hair follicles. Eurekalert. Available at: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-11/nlh-ssc110119.php.

No comments

Post a Comment