The National Institutes of Health has awarded a five-year, multi-investigator research grant expected to total more than $63 million to Mayo Clinic and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), to advance treatments for frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD).

FTLD is the overarching term for a group of neurodegenerative disorders that primarily affect areas of the brain associated with personality, behavior, memory and language. These disorders are estimated to account for 10%–20% of dementia cases in the U.S. Unlike Alzheimer's disease, which typically affects people over 65 and often progresses slowly, FTLD frequently affects people in their 40s, 50s and 60s who are still working and raising families. It often leads to rapid cognitive and physical decline, and death, in less than 10 years. There are no effective treatments.

The new grant merges two ongoing studies -; Advancing Research and Treatment in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (ARTFL) and Longitudinal Evaluation of Familial Frontotemporal Dementia Subjects (LEFFTDS) -; to form an integrated North American research consortium. The goal of the new ARTFL–LEFFTDS Longitudinal Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (ALLFTD) program is to advance cutting-edge knowledge essential for future treatment trials for patients.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration is devastating for patients and their loved ones. By working together in the ALLFTD program, researchers participating in this new consortium will be able to share data and foster development of disease-modifying therapies faster to help current patients and those who are risk for developing FTLD in the future."

Bradley Boeve, M.D., Mayo Clinic neurologist and co-principal investigator of the consortium

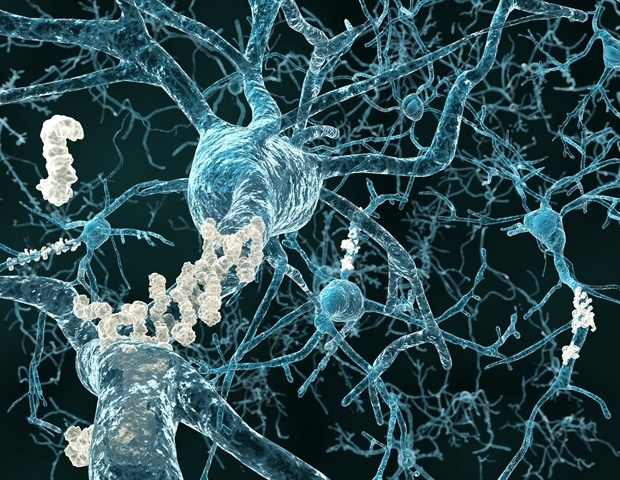

The related disorders grouped under the FTLD umbrella, including frontotemporal dementia, primary progressive aphasia, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal syndrome and related variants, all involve degeneration and shrinkage of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. However, patients have highly diverse clinical symptoms. Some people become socially inappropriate, impulsive or emotionally indifferent, while others lose the ability to use language, known as aphasia.

Other subtypes are characterized by problems with movement. As a result of this diversity, patients often initially are misdiagnosed with psychiatric or behavioral problems; movement disorders, such as Parkinson's disease; or Alzheimer's disease.

The causes of brain degeneration in FTLD are unknown, and more than half of patients have no family history of dementia. However, some subtypes have been linked to specific familial genetic mutations. The ALLFTD program allows researchers to directly compare familial and sporadic forms of the disease and presents an opportunity to build the scientific foundation for potential therapies across disease subtypes.

"We hope this will let us understand the whole course of illness -; from gene mutations to altered brain biology, and from the earliest to more mature symptoms of the disease," adds Howard Rosen, M.D., co-principal investigator and neurologist at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center and Weill Institute for Neurosciences. "Identifying early biological signatures of different forms of FTLD is key to beginning to test therapies designed to prevent or stave off the disease."

FTLD shares some common characteristics with Alzheimer's disease, including loss of neurons caused by toxic accumulations of tau and other dysfunctional proteins, but the underlying biology and genetics of FTLD are in many ways simpler and better understood. Therefore researchers are hopeful that powerful new therapies may be developed in the near future.

"This is an exciting time for FTLD research because we are poised to test a variety of novel therapies that have the potential to slow or arrest disease progression," says Adam Boxer, M.D., Ph.D., co-principal investigator and neurologist in the UCSF Memory and Aging Center and Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

"Because of strong genetic links and well-defined pathology in FTLD, we can be more precise about targeting new therapies to specific patients than in Alzheimer's disease, hopefully permitting us to find effective therapies for FTLD far more rapidly and efficiently, while at the same time making discoveries that could lead to treatments for both forms of dementia." Dr. Boxer is the Endowed Professor of Memory and Aging at UCSF.

North American clinical centers participating in the consortium are:

- Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland

- Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, Las Vegas

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Houston Methodist Hospital, Nantz National Alzheimer Center

- Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

- Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida, and Rochester

- Northwestern University, Chicago

- UCLA, Los Angeles

- The University of Alabama at Birmingham

- The University of British Columbia, Vancouver

- University of California, San Diego

- University of California, San Francisco

- The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

- University of Toronto

- University of Washington, Seattle

- Washington University in St. Louis

Clinical and neuropsychological measures will be submitted to the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center. Biospecimen samples will be stored at the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias at Indiana University in Indianapolis. Brain imaging data will be stored at the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Mayo Clinic

No comments

Post a Comment