The sheer abundance of noise that surrounds us makes it necessary for the brain to filter out selective components so that we can focus on what we need or want to hear. This is called filtering. When we hear two sounds that are exactly the same, the brain filters out the second sound by simply reducing the amount of nerve circuits that participate in its reception. This process is called auditory sensory gating (ASG). When a person has schizophrenia, ASG suffers disruption, which means a constant barrage of sounds hits the brain, preventing its concentrating on the vital sound elements. Now, a new study shows why this happens.

Auditory stimulus filtering not only allows the brain to concentrate on necessary elements but also prevent the dissipation of energy on unnecessary hearing tasks. The loss of ASG is therefore an extremely important part of efficient brain function. This filter begins to act just as soon as the auditory stimulus hits the brainstem, at the start of brain processing. Earlier, it was thought that ASG happens in the frontal cortex, at the front of the brain, which is involved in the last part of the auditory processing circuits in the brain – an area which is very dysfunctional in schizophrenia, a mental health condition found in 0.5% of people.

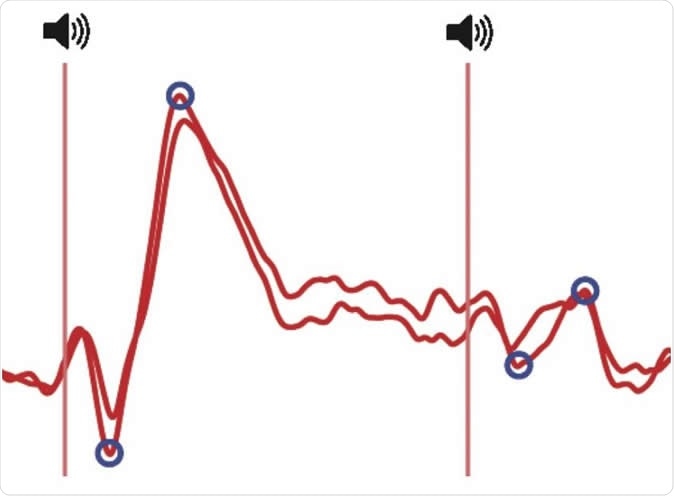

The loss of ASG has given rise to the simple P50 test for schizophrenia: exposing the patient to two identical sounds separated by 50 milliseconds (ms), while recording the resulting brain waves (called early evoked cortical responses) simultaneously by external encephalography. This test exploits the known difficulty of schizophrenics to separate, specify the priority and assign a rank to sounds from the environment. If the brain waves diminish steeply during the second sound, filtering has occurred successfully, but if highly similar waves occur both times, it’s characteristic of schizophrenia.

How was the experiment done?

To find out where ASG actually occurs, the researchers positioned external electroencephalographic electrodes on mice before the P50 test, but with the sounds separated by varying intervals from 125 ms to 2 seconds. Here too, the second sound failed to evoke nearly as much activity in the brain as the first, with the results closely resembling those of human experiments.

They followed up this experiment with internal electrodes, in the cortex and subcortical regions of the auditory part of the brain, which is spread over the brainstem to the frontal cortex. It is here that sounds are processed. The P50 was repeated with varying inter-sound intervals, and the scientists saw a clear drop in the attention paid by the brainstem to the second sound. The significant thing was that the electrodes showed that the drop occurred at brainstem level by 60%, rather than waiting until the signal reached the cortex. This means that the sound filter begins to operate as soon as the sound reaches the brain. The filtering effect increased from the bottom up until the cortex.

What did the study reveal?

The first sound not only produced an early evoked response which was transient, up to 100 ms in the mouse brain, but also triggered late activity in a series of consecutive neural networks, which lasted much longer, about 350 ms. This is far within the limit of ASG duration (500-2000 ms). If a second identical sound occurs during this period, the new sound is processed but does not overwrite or disrupt the ongoing activity. Once this is completed, the baseline waves resume and a second sound again evokes another cascade of network activation.

Researcher Charles Quairiaux says, “This discovery means we're going to have to reconsider our understanding of the mechanism.”

To understand this better, a repeat experimental set up is in progress using mice with the 22q11 deletion syndrome, where an important mutation that causes schizophrenia in humans is located. The aim is to see whether these mice show the loss of a filter at brainstem level as in humans with schizophrenia.

Early results showed that these mice had no obvious sound filtering mechanism for the second of two identical sounds at the brainstem. The researchers are excited – they could well be on the brink of discovering what causes one of the characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia.

The study is about to be published in the journal eNeuro.

Large-scale networks for auditory sensory gating in the awake mouse. eNeuro 2019; 10.1523/ENEURO.0207-19.20. https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0207-19.2019.

No comments

Post a Comment