Researchers at UC San Francisco (UCSF) and the University of São Paulo have shown that the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s brain pathology are tightly linked to neuropsychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, depression and sleep disturbances.

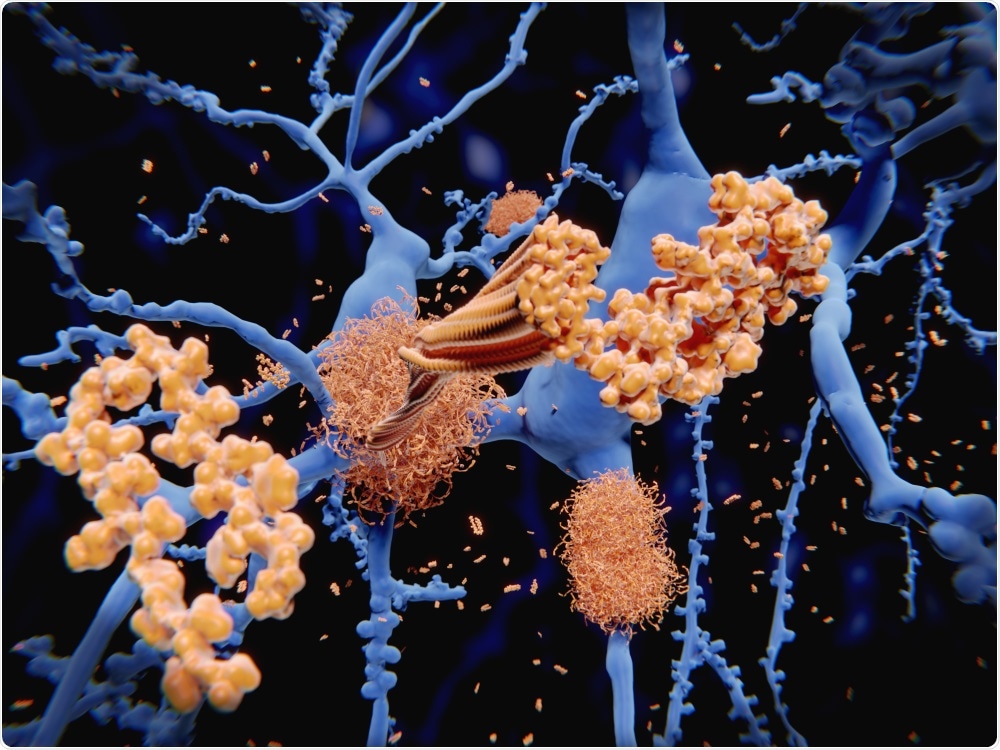

Shutterstock | Juan Gaertner

The finding strongly suggests that rather than such symptoms causing Alzheimer’s to develop, they are in fact the earliest warning signs that the disease is already in progress.

Study author Lea Grinberg says the discovery that the biological basis for these symptoms is the early Alzheimer’s pathology itself was quite surprising: “It suggests these people with neuropsychiatric symptoms are not at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease – they already have it.”

The authors say the findings could lead to earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and to biomarkers that could be used to develop drugs that would slow disease progression. They could also help researchers better understand the biological basis of psychiatric symptoms in older individuals.

Researchers are keen to treat early stage Alzheimer’s

Although Alzheimer’s disease is commonly associated with symptoms of memory loss and dementia, it is actually a progressive condition that can be detected by brain autopsy years before classic cognitive symptoms manifest.

Researchers are keen to develop treatments that could be administered in the earliest stages of the disease to protect against further loss of brain tissue and prevent the onset of dementia. However, this would require a more comprehensive understanding of the pathology underlying the initial stages of the disease and the ability to diagnose patients early enough to stop extensive brain tissue loss.

Many studies have already identified correlations between neuropsychiatric symptoms and an eventual diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and some researchers have even suggested such symptoms could serve as biomarkers of early stage disease. However, the relationship between the two has been unclear. Some scientists have proposed that psychiatric conditions or even the drugs used to treat them could themselves be the drivers that cause dementia to develop decades later.

Now, a study led by Alex Ehrenberg , who works in Grinberg’s lab at UCSF, has shown that the earliest stages of the brain degeneration associated with Alzheimer’s are tightly linked to the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Working with colleagues at the Brazilian Biobank for Aging Studies at the University of São Paulo, the researchers studied post-mortem brains donated by 1,092 seemingly healthy adults, aged over 50 years, who closely represented the general population of São Paulo. The researchers excluded 637 brains that exhibited neurological abnormalities not related to Alzheimer’s, which left 455 brains with either no signs of degeneration or a range of Alzheimer’s-related pathologies.

Disease progression

Pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease include an accumulation of neurofibrillary (NF) tangles made up of clumps of a protein called “tau” and the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aß) plaques, accompanied by brain tissue atrophy in associated regions.

Disease progression is nearly always the same, with NF tangles starting to form in the brain stem regions associated with emotional processing, appetite and sleep and Aß plaques accumulating in the cortical regions before later spreading to deeper brain regions.

Each of the 455 brains were assessed using standard scales of Alzheimer’s disease progression based on accumulation of the tangles and plaques. Statistical algorithms were applied to test for any association between Alzheimer’s stage and changes in the brain donors’ cognitive and emotional status before death, as reported by people such as relatives or caretakes who had been in at least weekly contact with the donors during the six months before they died.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms among those with earliest stages of NF tangles

Computational analysis of the results revealed that individuals with brainstems that displayed the earliest stages of NF tangles but who did not have memory changes reported by informants, did have increased rates of neuropsychiatric symptoms reported, including anxiety, agitation, appetite changes, depression, and sleep disturbances.

The next stage of disease where NF tangles accumulated in the brainstem and began to spread to other regions of the brain, was associated with an increased risk for agitation. Only in the later stages of disease, when the tangles started to reach the brain’s outer cortex, did donors demonstrate the signs of dementia and declines in cognition and memory that are typically seen in Alzheimer’s.

No link found between Aβ plaques build-up and neuropsychiatric symptoms

Importantly, no association was found between Aβ plaques build-up and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Researchers have long debated whether Aβ plaques or NF tangles play an earlier or more central role in driving the neurodegeneration seen in Alzheimer’s. The authors of the current study think these findings provide additional evidence that tau-targeted treatments should be a focus in Alzheimer’s research, especially since many of the results from recent trails of Aβ-targeted Alzheimer’s therapies have been disappointing.

“These results could have major implications for Alzheimer’s drug trials focused on early degenerative changes, where people have been seeking tractable clinical outcomes to target in addition to early cognitive decline,” says Ehrenberg.

He adds that the findings could also be valuable as more technologies emerge such as PET imaging of tau and blood biopsies for the detection of early stage Alzheimer’s pathology, which would help implement the novel biomarkers into clinical practice.

Using this knowledge to reduce burden in aging adults would be “absolutely huge”

Grinberg thinks the discovery that neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults may be linked to the accumulation of tau protein into NF tangles in the brainstem is as exciting as the implications for Alzheimer’s disease itself because, generally, the biological basis underlying most psychiatric conditions is not known. This stops physicians being able to do for these conditions what they can do for other conditions such as diabetes or cancer.

“They cannot say ‘You are having depression or sleep problems because of this disease in your brain, so let’s see if we can treat that disease,’” says Grinberg. “If we could use this new knowledge to find a way to reduce the burden of these conditions in aging adults it would be absolutely huge.”

No comments

Post a Comment