Breast cancer begins when the cells in the breast begin to grow out of control. The cells form a tumor, which can become malignant if they invade and spread to surrounding tissues. Like any other cancers, breast cancer has many risk factors that can’t be changed, like family history.

There are inherited genes that can cause cancer. An estimated 5 to 10 percent of breast cancer cases are thought to be hereditary. This means that they directly result from defects in genes, dubbed as mutations. The mutations can be passed from a parent to their children.

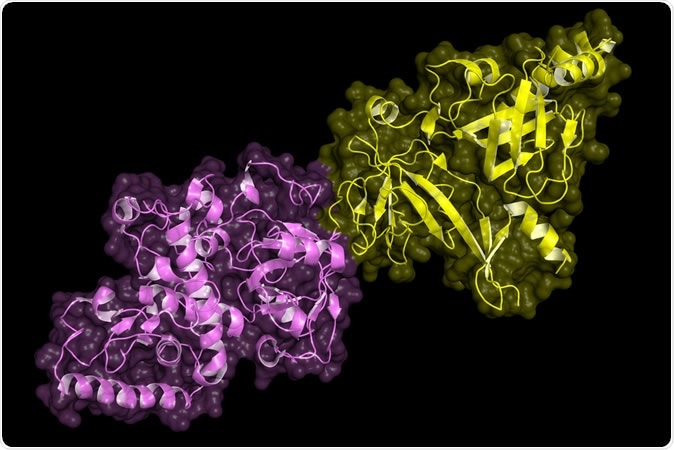

The most common cause of hereditary breast cancer are mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. These genes are important in producing proteins for DNA repair. If these genes undergo mutations, it can lead to abnormal cell growth and eventually, cancer.

Inherited breast cancer is harder to treat. Now, a team of researchers at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio may have found a novel therapy that can kill cancer cells in inherited breast cancer.

Light-switch for programmed cell death

A new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), found a molecule called microRNA (miR) 223-3p (MiR223-3p) prevents normal and healthy cells from making mistakes while repairing their DNA. In cases of cancers with BRCA1 mutations, this ability is repressed, hence, making the cancer cells divide.

MiR223-3p is like a light switch that can turn off the proteins that cancer cells need to divide properly. If they do not have the key proteins, the tumors commit suicide, termed as apoptosis or programmed cell death.

"It's a cool way of thinking about treatment. We are using the very nature of these BRCA1-deficient cancer cells against them. We are attacking the very mechanism by which they became cancer in the first place,” Dr. Robert A. Hromas, professor and dean of the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio, said.

When miR223-3p is restored before the cells become cancerous, it can prevent BRCA-1-related disease, he added.

BRCA gene mutations by the number

In the United States, about 1 in every 400 individuals, which is roughly equivalent to 825,000 people have BRCA gene mutations. The burden of the condition in South Texas and San Antonio are among the highest in the nation as the disease affects Ashkenazi Jews and Hispanics.

Inherited breast cancer still a global threat

The most common cause of inherited breast cancer is an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene. In cases where these genes are inherited, the risk of developing breast cancer is higher.

On average, a woman with a mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene can have about 7 in 10 chance of acquiring the illness by she turns 80 years old. The risk can still increase if there are more than one family members affected by breast cancer.

Also, the way that cancer risk is inherited relies on the gene involved. For instance, mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are passed down in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning one copy of the mutated gene in each cell is enough to heighten the risk of developing cancer. Although breast cancer is more common in women, the mutated gene can come from either the father or mother.

However, even if the mutated gene can be passed from one generation to another, not everyone with the gene will ultimately develop cancer.

Srinivasan, G., Williamson, E., Kong, K., Jaiswal, A., Huang, G., Kim, H., Scharer, O., Zhao, W., Burma, S., Sung, P, and Hromas, R. (2019). MiR223-3p promotes synthetic lethality in BRCA1-deficient cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). https://www.pnas.org/content/116/35/17438

No comments

Post a Comment